Down The Well: Alan Wake Remastered

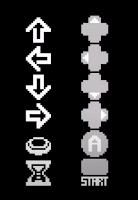

You're playing a video game.

As you navigate your character through three-dimensional space using the left analog stick on your controller, you're in constant conversation with the level designers; everything from lighting to the density and quality of props is drawing your eye, guiding you toward where the designers want you to travel in order to progress. The well-trodden path beneath your avatar's feet stands out against the more heavily leaf-strewn grass textures and scattered foliage ahead; in the same direction, a break in the fence geometry. Dark wooden slats contrast against the moonlit route forward.

This is where they're telling you to go.

Except, you've played enough games like this to know that they're NOT actually telling you where you should steer your character, the designers are telling you where the critical path is; where the rest of the level leads.

Unintuitively, because the ones shaping the space know that you're aware of this, that way won't be where the good stuff is. The extra ammunition, collectable tchotchkes, easter eggs, and everything about the game except for the ending inevitably lies along the side paths. In fact, jogging through that break in the fence and sliding down the next embankment might just break the invisible ticker tape of a cutscene, triggering a combat sequence that will unmake most of the landscape you just traversed; polygons and textures unloading themselves from random access memory to make room for your antagonists.

So to be safe, you travel everywhere BUT that way forward, just to make sure you've drawn every ounce of water out of the well that lies before you.

The metaphorical content well, of course; not that LITERAL well that they placed off the beaten path.

The extra bullets or snippet of lore tucked away near that prop are much appreciated; it turns out the gabled roof of the well probably exists just to signal the presence of those goodies.

Before moving back onto the critical path, you wonder why it wasn't worth someone's time to drop a circle of void into the skin of the world there. Maybe the level editor makes it difficult to align that hole with the prop. Perhaps the prop itself wasn't modelled with that kind of depth, and shining your flashlight down its construction would instantly reveal the artifice in an even less believable way than the well simply being dry and filled in to exactly the same level as the surrounding earth.

For whatever reason, trying to make the well feel real wasn't worth it.

But the problem with being this plugged into the meta-patterns of level design is that we're cursed to rub up against all these rough edges; especially if you've ever been a quality assurance tester. You can turn a player into a tester, you can even promote the tester out of QA, but good luck finding the player under all those patterns.

Those of us that habitually go the WRONG way, the completionists and explorers, the fellow developers, we're out here staring into your wells of content; secretly hoping to find voids that are real enough to stare back.

Comments

Post a Comment